The artworks that comprise the E.L. Wiegand Collection date from the early twentieth century to the present and represent various manifestations of the work ethic in American art. While many emphasize men or women undertaking the physical act of labor, others focus on different types of work environments ranging from domestic interiors and rural landscapes to urban cityscapes and industrial scenes. By expanding the definition of the term work ethic to encompass a broad range of activities undertaken by a diverse spectrum of people from various cultural and socioeconomic groups, the collection seeks to acknowledge all those who have devoted their lives to the tireless pursuit of work.

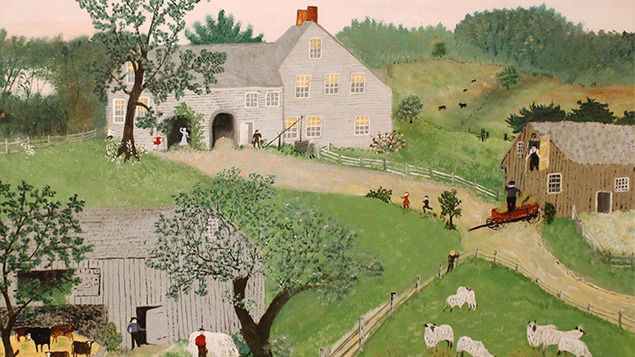

Over the past century, American artists have approached the subject of work from many points of view and with a variety of artistic styles. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, artists frequently chose to idealize scenes of work. Often this idealization took the form of agricultural landscapes featuring hard-working, farmers who epitomized the spirit of American democracy. During the 1920s and 1930s, this attention was re-focused on industrialization, and images of physically-fit, muscular workers came to symbolize the nation’s advanced industrial technology. Simultaneously, however, many Realist painters sought to convincingly portray the deplorable urban working conditions that were encountered by many of the nation’s poorest workers—a trend that continued during the era of the Great Depression, when artists shifted their attention to documenting the hardships faced by migratory, agricultural workers.

Perhaps the most influential event to impact the production of art in the United States was the launch of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal Program that was intended to put millions of unemployed Americans back to work in the 1930s. The inauguration of the Works Progress Administration (WPA)—a special fine arts component of the New Deal—aimed to employ thousands of artists across the country. While many of the paintings, sculptures, and public murals produced under the auspices of the program featured American men and women at work, the program itself helped to validate the important contributions artists make to society and formally invited them to join the venerable ranks of the American workforce.