This theme comprises one section of the museum-wide exhibition, Tahoe: A Visual History.

In 1844, trapper and frontiersman Elisha Stevens safely guided the first American emigrant wagons across the Sierra Nevada to California over what came to be known as Donner Pass. Two years later, the Donner Party sought to repeat this trek, but snow stranded them near the lake that would later bear the Donner name. Because of this disaster, a region destined to develop into a world-class destination first entered American history through a dystopian scenario of starvation, death, murder, and cannibalism.

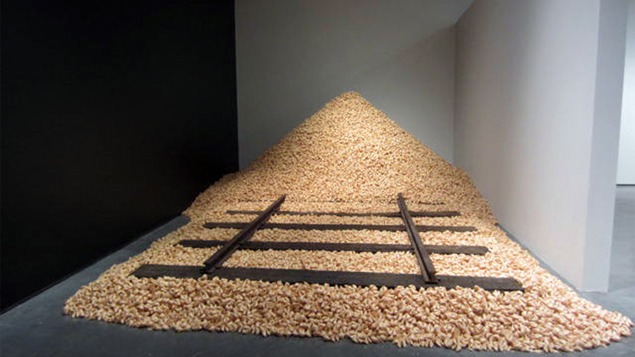

One might think that the tragedy of the Donner Party would have provided a warning for generations to come. In the American West, however, dystopia remained a recurrent possibility. The Sierra Nevada and Donner Pass stood as a barrier to America’s desire to expand westward. As the transcontinental railroad neared completion in 1869, over 20,000 men were employed by the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroad companies in some capacity. Around 12,000 of them were Chinese immigrants working in the treacherous Sierra canyons. Accidents, avalanches, and explosions, according to some reports, left as many as 1,200 Chinese laborers dead.

The nineteenth-century paintings and photographs of Donner Pass seen throughout this exhibition tend to offer romantic views of picturesque rail cars and pristine landscapes. Whether intentionally or not, artists typically marginalized or ignored the presence of Chinese workers. Many Chinese and Chinese-American artists working today seek to revisit this visual history, producing artworks in a variety of media to honor and memorialize the stories of those who perished during the construction of the railroad.